Life History and Ecology

Anadromous Atlantic salmon are a wide-ranging species with a complex life history. The historic range of Atlantic salmon occurred on both sides of the North Atlantic, from Connecticut to Ungava Bay, Canada, in the western Atlantic, and from Portugal to Russia’s White Sea in the eastern Atlantic, including the Baltic Sea. The generalized Atlantic salmon life cycle is illustrated in figure 4. Freshwater ecosystems provide spawning habitat and thermal refuge for adult Atlantic salmon, overwintering and rearing areas for eggs, fry, and parr, and migration corridors for smolts and adults (Bardonnet and Bagliniere 2000).

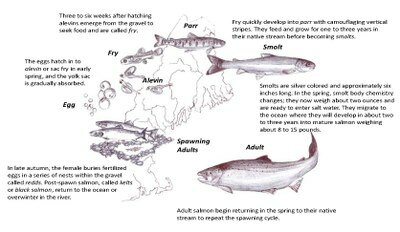

Figure 1. Life cycle of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Katrina Mueller, Project SHARE)

Adult Atlantic salmon typically spawn in October and November. During spawning, the female uses its tail to scour or dig a series of nests in the gravel where the eggs are deposited; this series of nests is called a redd. The eggs remain in the gravel until they hatch in late March or April. At this stage, they are referred to as alevin or sac fry. The alevin remain in the redd for about 6 more weeks and are nourished by their yolk sac until they emerge from the gravel in mid-May. At this time, they begin active feeding and are termed fry. Within days, the fry enter the parr stage, indicated by vertical bars (parr marks) on their sides that act as camouflage. Atlantic salmon parr are territorial and disperse upstream and downstream to suitable habitat to decrease densities. If suitable habitat is not available, dispersing juveniles may experience high mortality (Gee et al. 1978, Legault 2005). In particular, suitable overwintering habitat may limit the abundance of large parr prior to smoltification (Cunjak et al. 1998).

Smoltification usually occurs at age two for most Atlantic salmon in Maine. Each individual smolt has a brief emigration period lasting only 2 to 3 weeks. During this brief emigration window, smolts must contend with rapidly changing environmental conditions (freshwater to marine) and predator assemblages (McCormick et al. 1998, Mather 1998). Smolts migrate downstream, through the estuary, and into the ocean from late April through May.

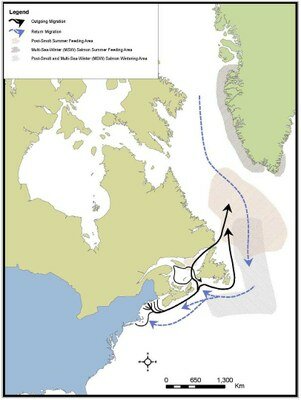

Upon entering the estuary and bay, smolts select areas of high tidal movements to aid in their migration (Kocik et al. 2009). Atlantic salmon smolts experience comparatively higher mortality rates through the estuary and inner bay than they do anywhere else along their migration journey between the river and the open ocean (Kocik et al. 2009). Increased mortality may be associated with the transition to salt water, zonal ecological differences, or a combination of the two (Tytler et al. 1978, Lacroix and McCurdy 1996, Stefansson et al. 2003). Developing adults generally spend from 1 to 3 years in the ocean. Upon entering the sea, Atlantic salmon smolts travel through the top 3 meters of the water column (Reddin 1985) and begin a migration northward into the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Grand Bank, and into the Labrador Sea (figure 5). Here, Atlantic salmon from the GOM DPS mix with other Atlantic salmon from Europe (see Fay et al. 2006). In the ocean, adult Atlantic salmon prefer cooler waters, 4° to 8°C (40° to 46°F).

Figure 2. Generalized marine migration routes of U.S. origin Atlantic salmon (from Tara Trinko Lake, NOAA).

In addition to anadromous Atlantic salmon, landlocked Atlantic salmon are native to four watersheds in Maine: the Union, including Green Lake in Hancock County; the St. Croix, including West Grand Lake in Washington County; the Presumpscot, including Sebago Lake in Cumberland County; and the Penobscot, including Sebec Lake in Piscataquis County (Warner and Havey 1985). Beginning in 1868, landlocked salmon were stocked extensively throughout the State to create or improve recreational fisheries. More than 51 million landlocked Atlantic salmon have been stocked in over 300 water bodies throughout Maine between 1937 and 1999 (Fay, et al. 2006, Warner and Havey 1985). Four state hatcheries raise landlocked salmon and today provide primary fisheries in 176 lakes. There are several lakes and rivers in Maine in which landlocked salmon and anadromous salmon coexist (e.g., East Branch Penobscot River). Genetic studies have confirmed that little genetic exchange occurs between these two life-history types (King et al. 2001, Spidle et al. 2003, summarized in Fay et al. 2006).

Document Actions